The Multiplicity of the Goddess

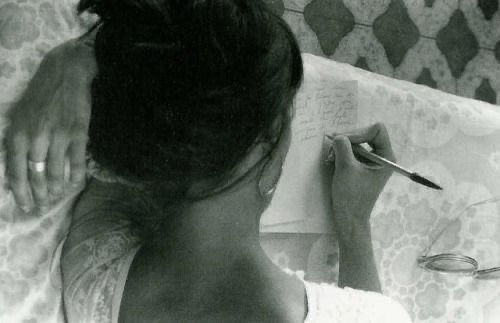

- Michelle Del Valle

- Oct 9, 2025

- 4 min read

The earliest known depictions of the divine are overwhelmingly feminine. The first sacred symbols we have, etched in stone, shaped in clay, were born from and centered around feminine power. These beginnings remind us that divinity has always been imagined in many forms, but most often, at first, as feminine.

What draws me most to the modern reclamation of the feminine narrative is how clearly it mirrors the goddesses themselves: never one-dimensional, but multifaceted, contradictory, expansive. Their stories travel across time and culture, reflecting the complexity of womanhood in all its forms. Myths echo the erasure of real women from history, yet they also forecast something deeper: a remembering of our power, depth, and contradiction.

The feminine is not singular, passive, or perfect. She is layered, contradictory, and ever-evolving, and it is this multiplicity that makes her divine.

My fascination with goddesses began early. I still remember seeing Uma Thurman as Venus in The Adventures of Baron Munchausen: radiant, sensual, and entirely (and mischievously) at the mercy of her husband, Mars. That image stayed with me. For years, I thought a goddess was either a beautiful muse or a jealous man’s possession. Those early impressions etched into me the idea that femininity meant softness, desire, and the duty to soothe another’s rage. Anger, especially my own, felt dangerous… something to suppress rather than feel or express.

Of course, life complicates things. The goddess is not only maiden or muse, but complex. She holds rage as well as tenderness, desire as well as discipline. Even softness changes depending on the circumstance.

When I first began exploring tarot and mysticism, I was drawn to The Goddess Tarot by Kris Waldherr. It became a doorway into stories from many cultures and times. Through its archetypes, I started tracing the threads that connect them, like how migration, cultural exchange, and even colonization reshaped their stories into the versions we know today.

When I think about the multiplicity of the goddess now, I find myself returning to Artemis. She can often be misunderstood, painted in black and white, stripped of nuance. Known as the Goddess of the Hunt, of virgins, and of wild animals, she is Apollo’s twin and later mirrored as Diana in Roman mythology. We often frame her independence and wildness as purely “masculine” qualities, forgetting the deeply feminine urge that underlies them: to protect, nurture, defend what is sacred.

But Artemis herself is not one goddess, but many. Over centuries her image can be found fused with others: Artemis of Ephesus, Kybele, and more. Fertility, protection, land, body: all layered within her mythology. Which is real? All of them.

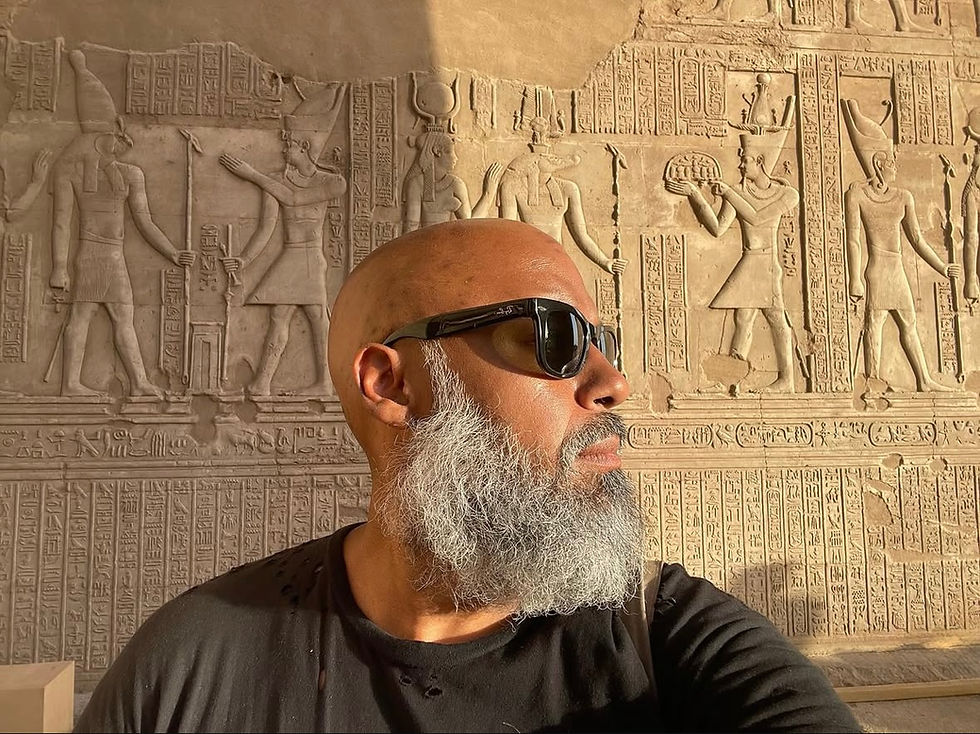

This is the heart of myth, how it’s told, who tells it, and why it still matters. In Western culture, we’re taught to see myth as fiction. Yet for generations, people prayed to these gods and goddesses, built temples, and wove their stories into ritual, survival, and the turning of the seasons.

One story that captures this idea is the sacrifice of Iphigenia. Versions differ, but the theme is constant: contradiction. Agamemnon, preparing to sail to war, is told he must appease Artemis to gain favorable winds. The price is his daughter’s life. Why would the protector of virgins demand the death of an innocent girl to serve a man’s thirst for conquest?

As the girl is brought to the altar, Artemis watches, not as a vengeful goddess, but as a witness to a ritual she may never have sanctioned at all. Just as the fire is lit, she intervenes. She replaces Iphigenia with a deer, carrying the girl away to become a high priestess in her temple: sacred, not sacrificed.

Other versions paint Artemis differently; cruel, complicit, merciless, and that too is part of her story. Her contradictions do not lessen her divinity; they deepen it.

This is the multiplicity of it all. Artemis is protector and punisher, merciful and merciless, worshipped as one goddess and remembered as another. She resists a single story. As does the feminine.

The myths remind me that the divine feminine has never been about perfection but about holding contradictions. To understand the goddess in her multiplicity is to remember that we, too, are many; that contradiction is not a flaw but a form of the sacred.

As I’ve grown, I’ve learned to honor those contradictions in myself. Multiplicity is not something to remove, it is something to embody.

Resources I Love

If you want to dive deeper into the goddesses and myths I’ve explored here, these are some of my favorite resources:

The Goddess Project by Dr. Carla Ionescu – Dr. Ionescu is one of the foremost experts on Artemis, Artemis of Ephesus, and many other goddesses. Her podcast and work are a treasure of insight, storytelling, and modern wisdom. She is, in many ways, a modern-day goddess herself.

Clytemnestra by Costanza Cosati – A retelling of the myth from Clytemnestra’s perspective, giving voice and agency to a character who is often sidelined. Women are no longer just the backdrop of epic stories but, in Cosati’s version, the backbone of the narratives we know.

Atalanta by Jennifer Saint – Atalanta, protected by Artemis, grows up wild, athletic, and strong. She is one of the few mythic heroines portrayed alongside men in epic adventures, living fully as her own character (a force to be reckoned with) rather than as a supporting figure.

Comments